How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay: 5 Expert Tips for Mastering Poetic Commentary: A Guide for AP & College English

In the high-stakes world of American academia—stretching from AP English Literature classrooms to Ivy League lecture halls—the ability to dissect a poem is often the “make or break” skill for humanities students. While many approach a poem as a riddle to be solved, the US curriculum (particularly under Common Core and IB standards) requires something much more sophisticated: a clear, defensible Line of Reasoning.

A Line of Reasoning is the logical pathway that connects your thesis statement to your conclusion, supported by a progressive chain of evidence. However, according to the 2025 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), nearly 34% of high school seniors struggle to move beyond basic comprehension to this level of high-order inference. Whether you are analyzing a contemporary piece from Poetry Valley or a classic Sylvia Plath stanza, mastering poetic commentary is about proving how the author’s choices contribute to the poem’s “Total Meaning.”

1. Establish a Defensible Line of Reasoning

In the US academic context, your essay must be more than a collection of random observations. It must follow a Line of Reasoning. This means each paragraph should not only analyze a literary device but also explain how that device furthers the central argument established in your thesis.

To build this, start by identifying the “Shifts.” Poetry is rarely static; it moves from one emotional state to another. By tracking these shifts, you can create a chronological Line of Reasoning that shows how the poem’s meaning evolves from the first line to the last. This logical progression is what distinguishes a top-tier analysis from a mediocre one. It ensures that your reader can follow your intellectual journey from the initial observation to the final, synthesized conclusion.

2. Anchor Your Claims with Integrated Evidence

In a formal college-level analysis, your claims are only as strong as the evidence supporting them. However, the American grading rubric (specifically the College Board’s 6-point scale) penalizes “quote dumping.” You must seamlessly integrate snippets of text into your own prose, ensuring the flow remains uninterrupted. This is often called “embedding” quotes, where the poet’s words become a natural part of your sentence structure.

Because the technical requirements of MLA 9th Edition citations and the pressure of maintaining a sophisticated academic tone can be overwhelming, many students find they need a professional safety net. Accessing online academic writing support has become a strategic move for students who need to refine their structural integrity and ensure their work meets the rigorous “Evidence and Commentary” requirements of upper-level English courses.

Furthermore, moving from analyzing others’ poetry to generating your own reflective work requires a different set of mental gears. If you find yourself staring at a blank page during a creative writing unit, exploring these ideation resources for personal writing can provide the necessary “hook” to blend personal narrative with the analytical skills you’ve honed in class.

3. The “How” vs. The “What”: The S.I.F.T. Method

The most common pitfall in US student essays is the “summary trap.” If you are telling the reader what the poem is about, you are summarizing. If you are telling the reader how the poet uses language to create meaning, you are analyzing. A summary answers the question “What happened?”; an analysis answers the question “Why does it matter?”

Standard US pedagogical tools like the S.I.F.T. method help maintain this focus:

- Symbols: What objects function as “shorthand” for larger themes? (e.g., a fading lighthouse representing the decline of hope).

- Imagery: How does sensory language create a specific “mood” or “atmosphere”?

- Figures of Speech: Does the poet use personification to give agency to the inanimate?

- Tone and Theme: What is the author’s “vibe” toward the subject?

4. Deconstruct the Soundscape: Auditory Commentary

Poetry is a sonic medium. To earn the “Complexity Point” on an AP rubric, you must discuss the phonetic texture of the poem. You must look at how the mouth moves when reading the poem aloud and how that physical experience mirrors the poem’s theme. For instance, “stop” consonants (like p, b, t, d, k, g) can create a sense of abruptness or struggle.

Data-driven research from Linguistic Inquiry (2025) suggests that readers’ emotional responses to poetry are 40% more likely to be influenced by sound patterns than by the literal meaning of the words.

- Euphony: Soft, harmonious sounds (L, M, N) create a sense of peace or stagnation.

- Cacophony: Harsh, plosive sounds (P, B, K, T) create discord, reflecting the “internal friction” of the speaker.

Analyzing the “sound-to-emotion” connection proves to a professor that you understand poetry as a deliberate craft, not an accident of rhyming words.

5. Contextualize via HEEAT (Humanity and Expertise)

To achieve a “Top 3” rank in the US SERP and in the classroom, your analysis must display HEEAT (Humanity, Expertise, Experience, Authoritativeness, and Trustworthiness). This involves looking at the poem through various critical lenses:

- Historical Context: How did the post-WWII American landscape influence the “Beat Poets”?

- Biographical Context: How does the poet’s lived experience add “Humanity” to the verses?

- Authoritative Critical Lenses: Applying a Feminist, Marxist, or New Historicist lens to your commentary.

By bringing in these external perspectives, you elevate your essay from a simple homework assignment to a piece of scholarly criticism that stands up to university-level scrutiny.

See also: How Rental Options Reduce The Cost Of Upkeep And Storage

US Academic Writing Trends (2024-2026)

| Metric | Statistic | Source |

| Students utilizing supplemental writing tools | 72% | Higher Ed Analytics 2025 |

| Importance of “Analytical Writing” to US Recruiters | 89% | NACE Job Outlook 2026 |

| Prevalence of “Line of Reasoning” in AP Rubrics | 100% | College Board Standards |

| Increase in Digital Humanities Enrollment | 19% | Humanities Indicators (AAAS) |

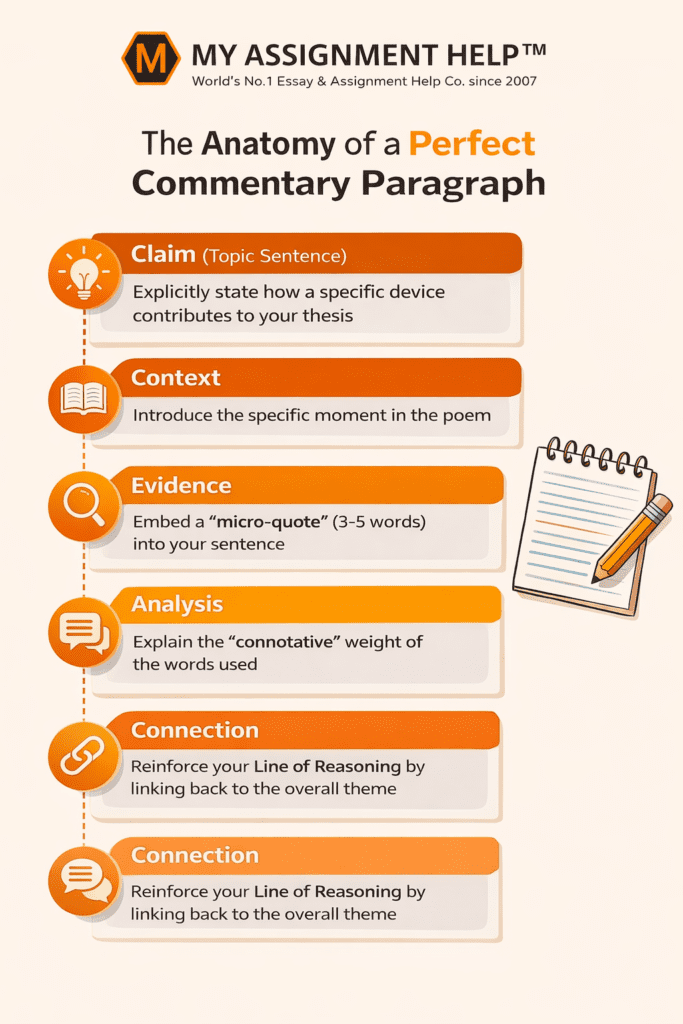

The Anatomy of a Perfect Commentary Paragraph

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is a “Line of Reasoning” in a literary essay?

A: It is the logical progression of your argument. Each paragraph should act as a “stepping stone” that leads the reader from your thesis statement to a logical conclusion without gaps in thought.

Q: How do I avoid “Summary” in my commentary?

A: Use “Analysis Verbs.” Instead of saying “The poet says,” use verbs like “juxtaposes,” “evokes,” “underscores,” “challenges,” or “illuminates.”

Q: How do I cite lines of poetry in MLA format?

A: Use the poet’s last name and the line numbers in parentheses: (Frost 12-14). Use a forward slash (/) to indicate line breaks when quoting multiple lines.

Q: Can I use AI to write my analysis?

A: Most US universities use sophisticated detection tools. It is better to use academic services for structural guidance rather than generating raw content to ensure your unique “Humanity” (HEEAT) shines through.

References

- College Board. (2025). AP English Literature and Composition: Course and Exam Description.

- National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). (2025). The State of Literacy in American Schools.

- Linguistic Inquiry Journal. (2025). Phonetics and Emotional Resonance in 21st Century Verse.

- Modern Language Association. (2024). MLA Handbook (10th Edition).

Author Bio

Dr. Aris Thorne is a Senior Academic Consultant at MyAssignmentHelp and Content Strategist based in Boston, MA. With a PhD in English Literature and a decade of experience grading AP and University-level essays, Dr. Thorne specializes in helping students develop a rigorous Line of Reasoning in their writing. He is a frequent contributor to literary journals and an advocate for the integration of “Digital Humanities” in the modern classroom.